The Nobel Prize in Physics is often awarded for discoveries that sound abstract, far-removed from everyday life. Yet every so often, a breakthrough arrives that quietly reshapes the foundations of tomorrow’s technology. This year’s prize is exactly that. The winning research explores some of the strangest behaviours in quantum mechanics – behaviours that, remarkably, can be observed in devices you could hold in your hand.

A prize for making the quantum world tangible

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has awarded the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics to three researchers: British physicist John Clarke, French scientist Michel H. Devoret, and American researcher John Martinis. Their award recognises their pioneering work on macroscopic quantum tunnelling and the quantisation of energy in electrical circuits – concepts that may sound daunting, but are far more accessible than they appear.

At its core, their work asks a fundamental question: how large can something be while still behaving according to the strange rules of quantum physics? Quantum mechanics usually applies to unimaginably small particles. But in the 1980s, these researchers carried out experiments proving that quantum behaviours can also appear in larger systems, visible without powerful microscopes.

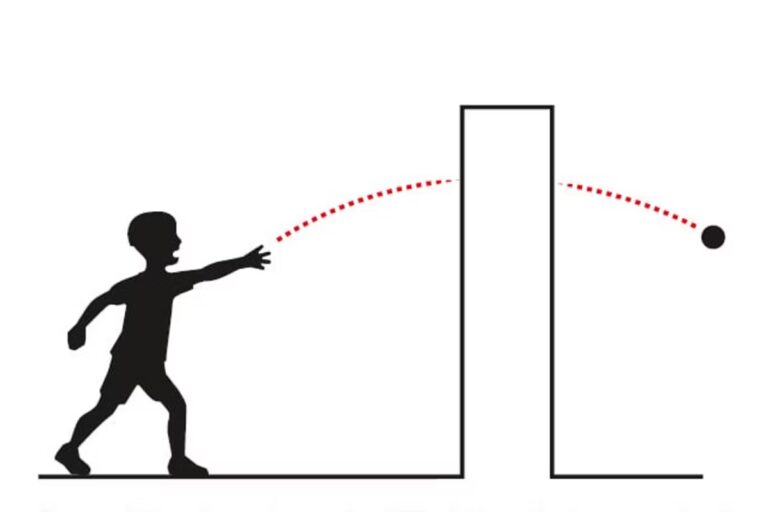

One example is quantum tunnelling. In the everyday world, if you throw a ball at a wall, it won’t magically appear on the other side. But in the quantum world, particles can sometimes do exactly that – slip through barriers as if by ghostlike shortcut. Clarke, Devoret and Martinis showed that similar effects can occur in specially designed electrical circuits, opening a door to entirely new technologies.

Why these discoveries matter for future technologies

The Nobel committee emphasised that these findings are not scientific curiosities but building blocks of modern quantum technology. Devices that rely on the behaviour of quantum states – from sensors to encryption systems – depend on exactly the phenomena Clarke and his colleagues explored.

For example:

- Quantum computers use quantised energy levels to process information in entirely new ways.

- Quantum cryptography relies on the fragile nature of quantum states, which collapse when intercepted, ensuring secure communication.

- Quantum sensors benefit from the extreme sensitivity of quantum particles to their environment.

The researchers’ work helped transform these ideas from theoretical speculations into engineering possibilities. The Nobel committee noted that their discoveries have “paved the way for the next generation of quantum technologies”.

A prize with historical echoes

This year’s award sits neatly within a broader trend. In recent years, Nobels in physics have increasingly celebrated research that bridges worlds: the microscopic and the macroscopic, the theoretical and the applied. Last year, the prize recognised Geoffrey Hinton and John Hopfield for foundational work on artificial neural networks, the backbone of contemporary AI. Their discoveries, made decades ago, now power systems used in medicine, translation, climate science and beyond.

Clarke, Devoret and Martinis’s work offers a similar long arc – research that began in the 1980s and now underpins a growing quantum industry.

What the laureates receive

As always, the prize comes with a diploma, a gold medal and a monetary award of 11 million Swedish kronor, roughly equivalent to one million euros. But perhaps more importantly, it comes with recognition that their experiments changed the way we understand – and use – the quantum world.

Why this Nobel matters

This year’s prize is a reminder that profound scientific advances aren’t always loud or flashy. Sometimes they begin with small, delicate measurements in quiet laboratories, revealing behaviours that defy intuition. And then, slowly, they reshape the future.

As quantum technologies continue to evolve, we may find ourselves using devices built on principles that Clarke, Devoret and Martinis first proved could exist on a scale we can see. In that sense, the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics doesn’t just honour past discoveries – it signals the horizon of what comes next.